Issue 23: There Are Morally-Depraved 8th Amendment Cases To Ridicule, Too

What You’ll Read

Vacancies & Elections: Progressive opposition to MA high court nominee; the MI Court of Appeals gets a public defender

There Are Morally-Depraved 8th Amendment Cases To Ridicule, Too. State supreme court contempt for SCOTUS should include awful rulings on criminal punishments

Cases To Watch: PA Supreme Court grants review in case challenging death-in-prison sentences; South Carolina Supreme Court hears arguments in firing squad case; former prosecutor Joe Deters, now on the Ohio Supreme Court, will decide his old case

ICYMI: MA high court orders prosecutors to investigate and disclose police misconduct — but “internal affairs” records remain off limits

And finally … New Mexico Supreme Court invokes the state Double Jeopardy Clause to bar retrial after prosecutor misconduct

Vacancies & Elections

In Massachusetts, Gov. Maura Healy decided that her ex-girlfriend, a former Big Law partner who defended pharmaceutical companies, is the single “most qualified” person to serve on the state’s highest court. On February 7, she nominated Court of Appeals Judge Gabrielle Wolohojian to the remaining vacancy on the Supreme Judicial Court, prompting the Boston Globe to lament the “awful” optics and blatant conflict of interest: “it beggars belief to imagine that the judge has no ‘personal bias,’ positively or negatively, toward her ex—who is arguably a party in all manner of lawsuits involving state government.”

In Balls & Strikes, Molly Coleman points out that Healy tabbed yet another corporate lawyer for a court without a single former public defender or civil rights lawyer who spent their career advocating for working people. The pick sends “a clear message that the judicial nominations process isn’t actually about elevating the person most likely to advance justice, but about advancing those who serve corporate power and know the right people,” Coleman wrote. Whether Wolohojian takes the bench, though, depends on the The Governor’s Council, which must confirm high court nominees and is scheduled to consider the nomination on Wednesday.

Contrast Healy’s approach to that of Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, who last month appointed appellate public defender Adrienne Young to the state Court of Appeals (the state’s intermediate appellate court). As an appellate advocate who appeared before the Michigan Supreme Court, Young was integral to historic rulings that expanded state constitutional rights against excessive criminal punishments, including protecting young people from death-in-prison sentences.

There Are Morally-Depraved 8th Amendment Cases To Ridicule, Too

In the last month, the state supreme courts in Pennsylvania and Hawaii rightfully made big, attention-grabbing shows of not just rejecting but openly mocking two widely despised U.S. Supreme Court decisions — they issued bold, clear-eyed opinions that drip with disdain for how the current Court prioritizes culture war posturing over serious constitutional analysis.

On February 7, the Hawaii Supreme Court ridiculed the “history and tradition” behind the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 decision that effectively created a super-right to carry guns. “History by historians quickly debunked [the Supreme Court’s] history,” the court said. And more over, “it makes no sense for contemporary society to pledge allegiance to the founding era’s culture, realities, laws, and understanding of the Constitution.” The court added a quote from The Wire for good measure: “The thing about the old days, they the old days.” Though the Hawaii Constitution mirrors the Second Amendment, the court rejected a state constitutional right to carry firearms in public. Instead, it said, the “spirit of Aloha clashes with a federally-mandated lifestyle that lets citizens walk around with deadly weapons during day-to-day activities.”

Similarly, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court last month issued what Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern at Slate called a “devastating rebuke” of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision that erased the right to abortion:

The majority vehemently rejected Dobbs’ history-only analysis, noting that, until recently, “those interpreting the law” saw women “as not only having fewer legal rights than men but also as lesser human beings by design.” Justice David Wecht went even further: In an extraordinary concurrence, the justice recounted the historical use of abortion bans to repress women, condemned Alito’s error-ridden analysis, and repudiated the “antiquated and misogynistic notion that a woman has no say over what happens to her own body.”

At issue was Pennsylvania’s ban on Medicaid coverage for abortion, which the court found to be sex discrimination that “presumptively” violates the state constitution.

In these cases, state constitutions provided legal grounding for state supreme courts to both express and act on outrage over the U.S. Supreme Court’s most morally-depraved and legally-flawed decisions. But state courts shouldn’t stop with guns and abortion, or with the most recent cases. The Court’s worst 8th Amendment cases should get similar treatment.

Despite the “cruel and unusual” clause that should limit criminal punishments, the Court has rubber stamped even the most extreme and cruel-by-any-measure prison terms. Twenty-five years to life for stealing pizza? Decades in prison for stealing video tapes, golf clubs, or a few hundred dollars? Life without parole for drug possession? All upheld by the Supreme Court. This hands-off approach is, law professor Rachel Barkow wrote, “one of the worst judicial abrogations of constitutional rights in the country’s history,” and as a result there are now over 200,000 people who are effectively warehoused on life terms.

And while the Court has imposed some limits on capital punishment, it has also allowed states to torture people to death — condoning “the chemical equivalent of being burned at the stake,” and, most recently, death by “agonizing and painful” nitrogen gas asphyxiation. In fact, under current law, a method of execution can only be challenged if the person sentenced to die presents the state with an alternative method by which to be killed.

These are repugnant rulings, and instead of citing them as reason to allow, say, 12 years in prison for bringing a cell phone into the county jail, state supreme courts should forcefully condemn and deride them, and invoke their state’s own anti-punishment clauses to reach different results.

Cases To Watch

Big news from the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which agreed to decide whether life without parole sentences in “felony murder” cases — that is, where someone neither killed nor intended to kill anyone — violate the state constitutional ban on “cruel” punishments. [JURIST | The Nation feature story | Docket]

I previously wrote of the pending petition:

In Pennsylvania, 70% of the more than 1,100 people serving life without parole for felony murder are Black. One of them, a man named Derek Lee, has petitioned the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to rule that his mandatory life (or “death-in-prison”) sentence for felony murder violates the state constitution’s ban on “cruel” punishments. Lee’s petition argues that Pennsylvania’s constitution must be construed both independently from and more broadly than the 8th Amendment, and that … under any standard, … the complete disconnect between felony murder and any legitimate penological purpose renders his life sentence unconstitutional.

A similar case is pending before the Colorado Supreme Court, and dual rulings that bar death-in-prison sentences could not only save more than 1,000 lives, they would signal a new and growing willingness of courts to limit excessive prison terms.

Related Scholarship: In the latest issue of the Penn Journal of Constitutional Law, lawyer Kevin Bendesky dives deep into the history of Pennsylvania’s anti-punishment clause, finding that it was born of Enlightenment Philosophy that prioritized — and even mandated — rehabilitation as the goal of criminal punishments. Moreover, Bendesky explains that Founding Pennsylvanians intentionally adopted an evolving standard, one subject to changing norms and scientific advancements on the efficacy of criminal punishments: “Evidence abounds that Pennsylvanians originally understood Section 13 to mean ‘cruel . . . for the age in question,’” he writes. “Revolutionary Pennsylvanians believed that ‘cruel’ punishments were those not necessary for rehabilitating offenders and deterring others according to contemporaneous morality and science.” [Read The Full Article]

While the U.S. Supreme Court has allowed execution by torture, the South Carolina Supreme Court will decide if executing people by firing squad or the electric chair violates the state constitution. In 2022, a state trial court struck down both methods as violating the state’s ban on “cruel,” “unusual,” or “corporal” punishments. “In 2021, South Carolina turned back the clock and became the only state in the country in which a person may be forced into the electric chair if he refuses to elect how he will die,” the court wrote. “In doing so, the General Assembly ignored advances in scientific research and evolving standards of humanity and decency.”

The state supreme court heard arguments in the state’s appeal on February 6. So far, state supreme courts in Georgia and Nebraska have held that electrocuting people to death violates their respective state constitutions. [Courthouse News (recap) | State Court Report (preview)]

The Ohio Supreme Court will again rule on the use of consecutive prison terms — addressing both trial courts’ discretion to impose them and appellate courts’ power to overturn them when excessive. In December 2022, before Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor retired, the court ordered trial courts to assess the need for consecutive sentences in the aggregate, and to ensure that the total sentence imposed is proportional to someone’s crimes and to sentences imposed for other offenses in the state. But last year a new conservative majority led by former prosecutor Joe Deters reversed that ruling, and upheld a de facto life term for a string of wholly nonviolent, small-time nursing home thefts.

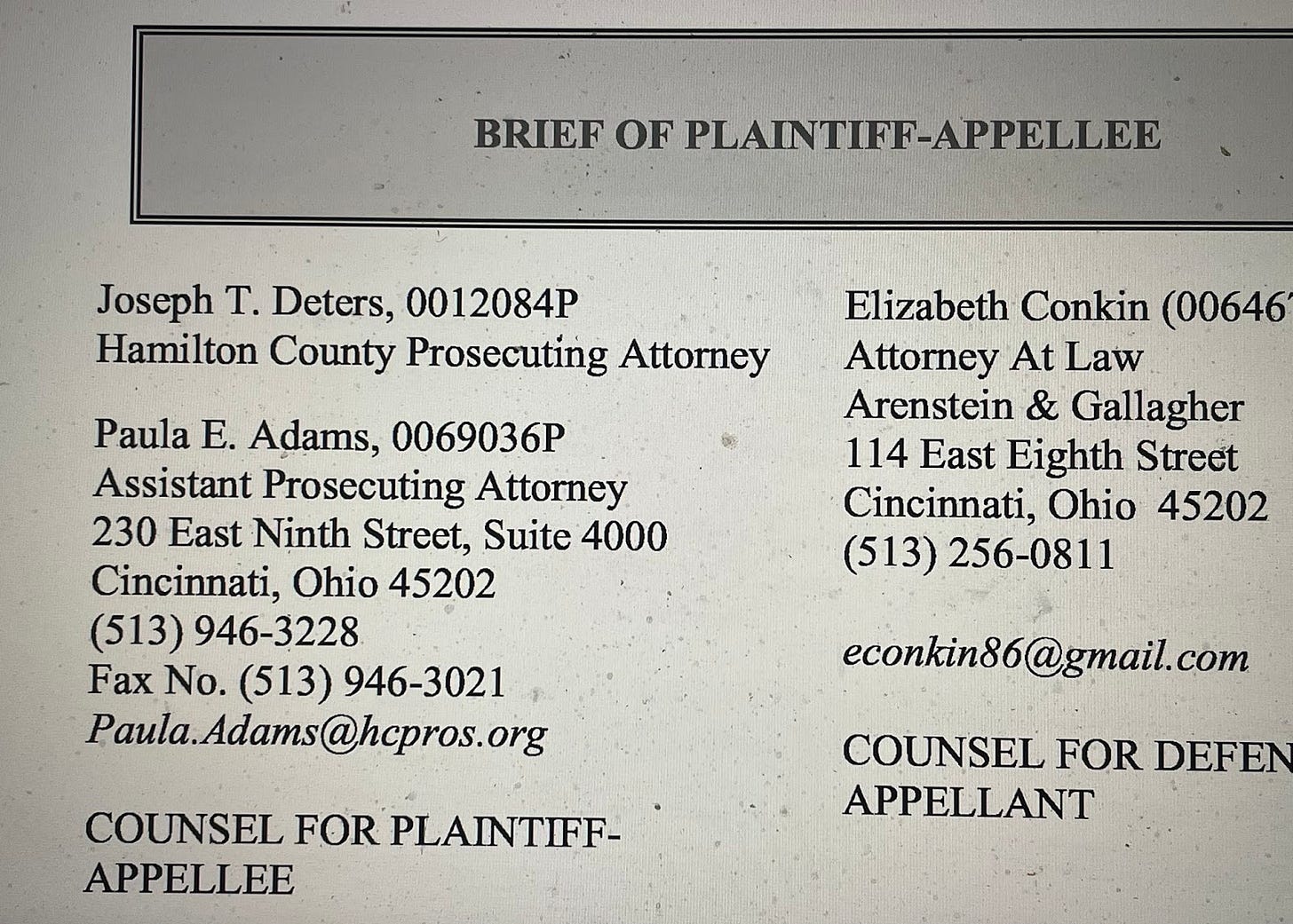

Last year’s ruling sparked controversy in part because the court redecided a case based only on a change in personnel, not the law. It was raw politics dressed up in legalese and judicial letterhead. But this time the optics are even worse. Deters did not recuse from the latest case, State v. Glover, even though he was the head prosecutor during Glover’s prosecution and was listed as counsel for the state when it opposed Glover’s appeal in a lower court — the very appeal now before him, and in which he may cast the deciding vote.

In a statement, Deters said that he did not recuse because he “did not participate personally or substantially in [Glover’s prosecution] and did not express an opinion about it” while county prosecutor. [Docket | Courthouse News Ohio | Yahoo! News]

ICYMI: Massachusetts High Court Orders Prosecutors To Investigate & Disclose Police Misconduct

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice investigated the Springfield, Massachusetts police department and found that officers routinely falsified police reports and engaged in a “pattern or practice” of covering up excessive force. Such rampant dishonesty raised serious doubts about the evidence that the Hampden County District Attorney’s Office used to obtain convictions, and whether prosecutors had adequately disclosed information about discredited officers to defense lawyers and their clients.

A lawsuit brought by the Committee for Public Counsel Services and the Hampden County Lawyers for Justice alleged that the damning pattern or practice report imposed affirmative duties on local prosecutors that they routinely failed to meet. On January 23, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court agreed, citing both state rules of practice and the obligation to disclose exculpatory evidence under Brady v. Maryland to “reemphasiz[e] the importance of a prosecutor’s dual duties — to disclose and to investigate — in upholding the integrity of our criminal justice system.” And the court found that Hampden County prosecutors failed these duties in at least three ways: by disclosing findings of dishonesty only on a discretionary basis; withholding evidence of police misconduct when they did not know (and did not bother to investigate) which particular officer committed the misconduct; and failing to obtain all of the documents that had been reviewed by DOJ.

The ruling may be the first to impose clear duties on prosecutors after a federal investigation into local police, and is a major win for due process that properly places the burden of identifying dishonest officers on the prosecutors who would rely on their testimony to send people to prison.

Still, the court also affirmed precedent that conceals internal affairs records from prosecutors’ investigations into officer misconduct. In a 2015 law review article, Jonathan Abel identified such material as “Brady’s Blind Spot.” He argues that “critical impeachment evidence is routinely and systematically suppressed as a result of state laws and local policies that limit access to … personnel files,” and that such “privacy protections for police misconduct are incompatible with core aspects of the Brady doctrine.” In Massachusetts, it is now clear that prosecutors have an affirmative duty to investigate and disclose police misconduct, including misconduct subject to a DOJ pattern or practice investigation. But the promise of Brady remains unfulfilled if some police misconduct remains buried in confidential personnel files.

And finally . . . After prosecutor misconduct caused a mistrial, the New Mexico Supreme Court held that the state constitution’s Double Jeopardy Clause barred a second trial and ordered the trial court to “to vacate Defendant’s convictions and discharge Defendant from any further prosecution in this matter.” [State v. Amador]